17 Heriot Row

(1857 – 1880)

The large Georgian townhouse at 17 Heriot Row, which was built between 1802 and 1806, is where Robert Louis Stevenson stayed for the rest of the time that he lived in Edinburgh. It was definitely a move up in the world for his family in terms of comfort and status. It was also literally a move uphill to a much higher point in Edinburgh, away from the harmful pollution of the Water of Leith. (I should perhaps add at this point that the Water of Leith is now a beautiful, clean river, and walking alongside it, especially on a summer’s day, is an absolute delight.)

Heriot Row is situated in Edinburgh’s New Town, which is only ‘new’ in comparison with Edinburgh’s mediaeval Old Town. The New Town was actually built between 1767 and 1850. It was intended to relieve the terrible overcrowding in the Old Town and to discourage its more wealthy residents from moving to London. As a result, the rich moved from their cramped dwellings into beautiful spacious Georgian homes on much wider streets. The poor, of course, didn’t have that luxury. As Stevenson was later to write in Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes: ‘From their smoky beehives, ten stories high, the unwashed look down upon the open squares and gardens of the wealthy’. This was simply an observation, not a judgment of any sort. RLS tended to feel the heart and soul of Edinburgh was in the Old Town. He was to spend much time there during his student days.

Fortunately for the Stevenson family, they could afford to live in the New Town. Thomas Stevenson was an outstanding marine engineer, lighthouse designer and meteorologist. He also served as president of the Royal Scottish Society of Arts, president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and was cofounder of the Scottish Meteorological Society. He was an enormously accomplished and successful man.

The house at Heriot Row was ‘not only gay and airy, but highly picturesque’, as RLS wrote in later years. A beautiful and substantial home, it overlooks Queen Street Gardens, which only residents can access and where Robert Louis Stevenson would undoubtedly have played as a boy. The entire street is virtually untouched since it was constructed in 1802.

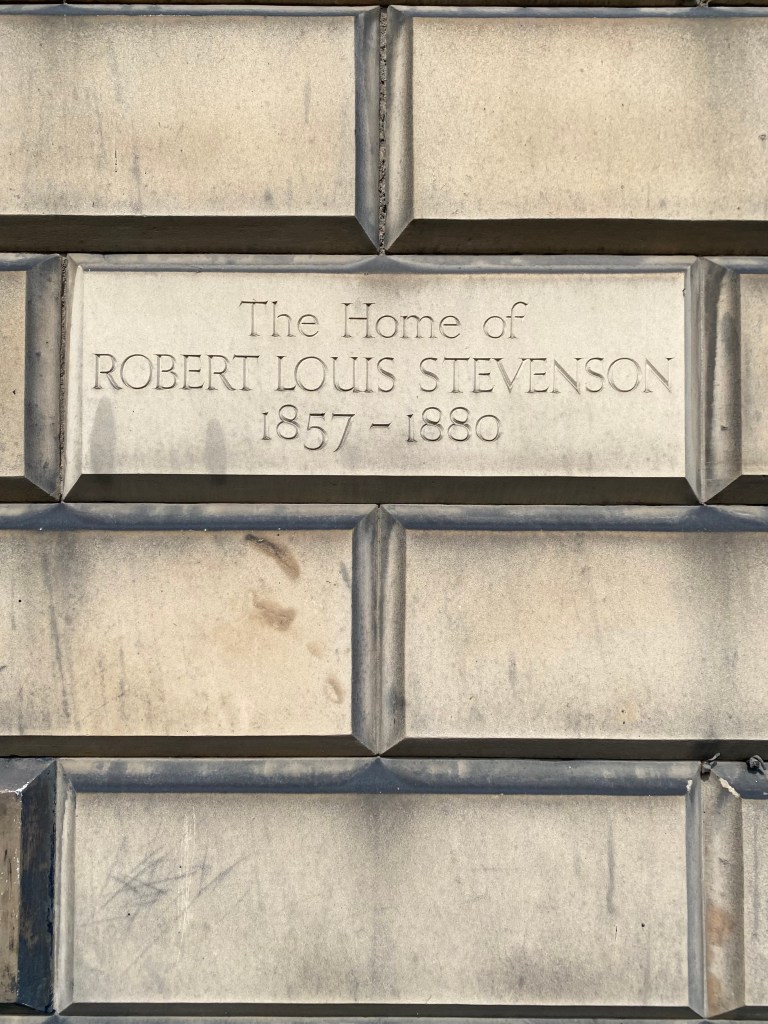

As with the house at Howard Place, there’s a stone plaque on the wall at 17 Heriot Row indicating that Robert Louis Stevenson once lived here:

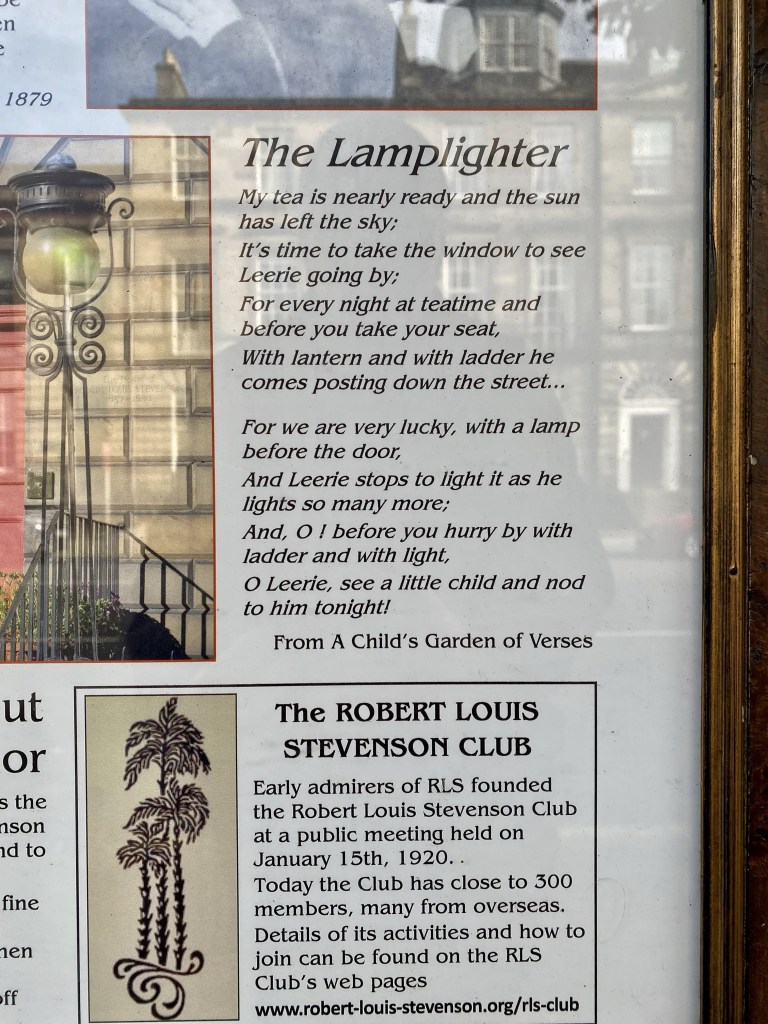

And next to the steps that lead up to the bright red front door of the house, there’s a brass plaque beneath a beautiful Georgian-style street lamp featuring a verse from “The Lamplighter”, a lovely little poem RLS wrote in 1885 and published in his delightful book of poetry A Child’s Garden of Verses.

Only the last four lines of the poem are inscribed on the plaque, but the entire poem is worth quoting, describing as it does a sight the young boy must have seen many times from the windows of this house:

My tea is nearly ready and the sun has left the sky;

It’s time to take the window to see Leerie going by;

For every night at teatime and before you take your seat,

With lantern and with ladder he comes posting up the street.Now Tom would be a driver and Maria go to sea,

And my papa’s a banker and as rich as he can be;

But I, when I am stronger and can choose what I’m to do,

Oh Leerie, I’ll go round at night and light the lamps with you!For we are very lucky, with a lamp before the door,

The Lamplighter by Robert Louis Stevenson

And Leerie stops to light it as he lights so many more;

And O! before you hurry by with ladder and with light,

O Leerie, see a little child and nod to him tonight!

According to John Mcfie, the current owner of 17 Heriot Row, the Lamplighter had to rush by as he had to light a certain number of lamps in a limited period of time or his wages would be docked. This would explain why he never noticed or nodded to the little boy in the window.

Sadly, although his living conditions improved at Heriot Row, Stevenson’s health continued to give concern:

‘‘My ill-health principally chronicles itself by the terrible long nights that I lay awake, troubled continually with a hacking, exhausting cough, and praying for sleep or morning from the bottom of my shaken little body. I principally connect these nights, however, with our third house, in Heriot Row … ”

It was at these times that Cummy showed her great capacity for tenderness:

“It seems to me that I should have died if I had been left there alone to cough and weary in the darkness. How well I remember her lifting me out of bed, carrying me to the window, and showing me one or two lit windows up in Queen Street across the dark belt of gardens; where also, we told each other, there might be sick little boys and their nurses waiting, like us, for the morning.”

The combination of Stevenson’s poor health, his father’s contempt for schools and teachers, and both of his parents’ hypochondria meant that he was often at home. His mother wrote that he ‘was too delicate to go to school’. However he did attend Mr Henderson’s private school at 36 India Street, at least briefly, and Edinburgh Academy for a while. He also had a private tutor from England at one point but that didn’t last for long. Cummy provided informal lessons for months at a time when Stevenson wasn’t attending school. When he was 12 years old, his parents, who were spending time in Europe for health reasons, enrolled him in a boarding school in Surrey, but RLS was keen to be reunited with his family. Later he attended Mr Thomson’s school at 40 Frederick Street in Edinburgh, where he remained until he went to the University of Edinburgh.

The Stevensons were an extremely successful family of civil engineers, specialising in lighthouses, and Thomas Stevenson wanted his son to become an engineer too. So, during his time at university, Robert Louis Stevenson studied engineering and spent three summers as an apprentice with the family firm, where he travelled along the Scottish coast to learn about marine engineering projects. Possibly the only experience he really enjoyed during this apprenticeship was when he descended in a Victorian-style diving suit into the choppy waters of the harbour at Wick. This he found exhilarating. But engineering wasn’t the life RLS wanted for himself. He had no real interest in it, no enthusiasm for it.

During a difficult conversation one evening, Stevenson told his father that he cared for nothing but literature. Forced to accept that his son would never follow in the family profession, but bitterly disappointed, Thomas insisted that he should train for an equally respectable career – an alternative should the “devious and barren path of literature” not work out. Despite having as little interest in it as he had in engineering, RLS acceded to his father’s wish and set out to study law at Edinburgh University. Rather amazingly, in 1875, he was called to the bar. But despite qualifying, he appears only to have appeared in court once. Law was not to be his future.

Instead, he travelled the world and wrote some immensely popular novels, short stories, travel books and poems, many of which are still widely read today. In spite of his chronic ill-health, he lived an adventurous and creative life, and married a woman he loved deeply, an American called Fanny Osbourne. He died of a stroke at the age of 44 in Samoa, an island in the South Seas where he spent the last four years of his life with his wife. There he had been a popular and highly respected figure. In accordance with his wishes, he is buried on the summit of Mount Vaea. Based on his own poem, Requiem, the following epitaph is inscribed on his tomb:

Under the wide and starry sky

Dig the grave and let me lie

Glad did I live and gladly die

And I laid me down with a will

This be the verse you grave for me

Here he lies where he longed to be

Home is the sailor home from the sea

And the hunter home from the hill

CONGRATULATIONS: A wonderfully crafted narrative accopanied by high calibre sensitive photography.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Rex!

LikeLike